Every book tells a story.

I'd never write that. Not every book tells a story (let alone a good story, duh!), and precious few elicit stories, unlike dreams. The books I've reviewed so far here, from my collection, elicit memories, the only material used by people to make stories. Although sometimes they use photographs. I don't like stories or photograph. I like movement! It's Easter, which always feels like the end of the world to me. Lama sabachthani. I feel interned, having sat through yet another assault of “contemporary theater” this weekend. So I retreat to my substack, like some hillbilly (I am that I am) whose just heard on the radio that some King Ferdinand has just been killed by a man with an even more inscrutable name in some place called Europe. Truth holds no account here, and that comforts me, as well as my sheep. Truth is made or unmade by a “system to pointing,” as Stein would say. A tracing, not a map.

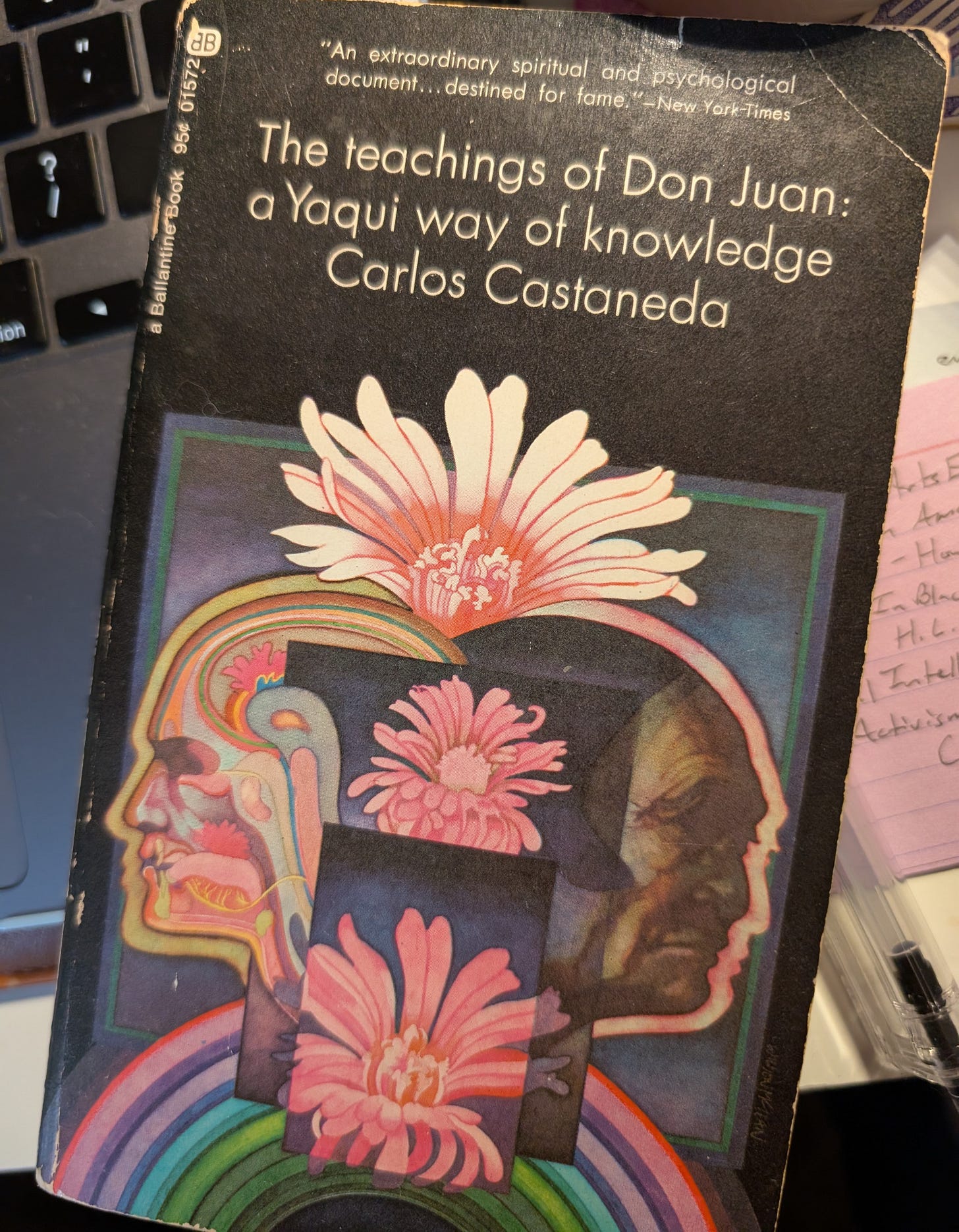

What exactly was I looking for, ten years ago, when I came upon a set of Castaneda’s first three books in a little free library in Providence and took one out, each day, as I walked to work? Providence? I wasn't looking for providence, I was looking for news ways of describing experiences I never had. Or experiences, though experienced, I could never be said to have possessed--like dreams.

I began to narrate to him the sequence of my experiences from the beginning but he interrupted me saying that all that mattered was whether I had seen him or not.

I had begun, around 2017, to have what I thought were visions. To say visions of the future would be incorrect, because I had read enough about time at that point to understand that past and future were just other planes (or panes?) through which we viewed the present as present, as being here by intuiting a there. A fiction. This is the year I watched The Leftovers in preparation (spiritual preparation) for Twin Peaks: The Return. Each made me ask questions is never asked before. Each made me want to start lifting weights. And each made me think--for no other reason than the way mental concepts are connected to others in irrational ways--about Australia. I had read somewhere that new broadcasts of 9/11 were on screen at the Sydney airport a full 20 minutes before the attacks actually took place. Again, the way things connect to other things (subterraneanously or transcendentally) always has more to do with time than space.

Sarah Nicole Prickett’s diary of The Return became a model for me. In fact, her column had been one of the most forceful inspirations in my turn to diaristic prose, an escape from Poetry 's non-discursive madness. Prickett remains, perhaps, one of my top five favorite contemporary writers. I feel dysphoric jealousy looking through her Instagram, reading the ease with which her paragraphs transition into the next into the next. Nora hates her, I think, not just because of her writing, but because of my covetousness towards her and her life. She's one of those people who can write about anything. I only ever tend to write about anything other than the thing I've set out to write about. I've always wanted to get paid to write about women's shoes (an obsession since childhood). Maybe if Song Cave puts out an anthology of poems about women's I'll be able to knock out two birds with one stone.

I didn't have to take peyote for these visions but reading about someone's (probably made up) visions of what might be possible to see through the blindness of sensory disruption was instructive. Castaneda's narrative, told mostly through inane dialogues between an idiot grad student and an awfully drawn wise man, relies on almost subterranean dramatic tension. When the narrator sees a dog during one of his visions, it's the most terrifying dog because no one expected it. This isn't surrealism, though. It's a metaphorics of the everyday. Any resolution--on the narrator's behalf or the reader's--deoends on an indelicately honed plan of reaction. I started breathing differently. I started going on these walks I called “Thinking,” where I'd look at an object and think of its further associative cognate. Somehow, when I would call a doorknob a “an opening where gold resisted,” it brought a reality back into view. Is there anything to hold onto?

My fellow children's librarian at the time and I shared a beautiful agony of shared attraction. Most of the hours our days together consisted of us stock-still at our adjacent computer terminals, touching, I liked to believe, through the particles of sweat emanating from our nervous pits just before evaporating in the space between us. Eventually, it would be 10 o'clock and we’d negotiate whose turn it was to run storytime. Our supervisor said “As long as you're working on something, I don't care what you're doing.” I wrote 1,000,000 poems. I wrote to keep myself clean. She once told me she thought people who were attracted to feet belong in prison.

I often had to remind myself that there is only one timeline and that I didn't own a single second of it. Maybe, all along, she had been quietly tolerating me, a pretentious psycho who kept bringing books about drugs to a children's library. But that can't be true. We definitely had our moments. She never asked about any of the technicolor trade paperbacks I kept propped behind my keyboard, but I obviously wanted anyone to ask. The book ends and the narrator's like, “I'm not sure what I learned but I could sure use some damn PEYOTE right about now!” At least, that's my vision of how it ended. After it's stratospheric success among hippies and French intellectuals, Castaneda wrote so much more. At the end of his career, I suspect he started forgetting where the light came from.

~

I'm still not sure what madness means or if I've ever felt anything close to history’s great mad-hatters. I've been called a megalomaniac, lazy, too horny (all of which seems to contradict each other), and, perhaps most often, a bad storyteller. But I've never been called a liar. Or never been caught.

substack entreated me to ‘pledge’ my support

Came for the feet stayed for the fun